The term hypermobility is one easily conceptualised by the general population, there is increased movement beyond the ‘normal’ joint range of motion. Hypermobility has historically dominated the sphere of gymnastics, dance and acrobatics as advantageous skill acquisition. Outside of acquired hypermobility which is often used for performance gains, there is a spectrum of hypermobility disorders from asymptomatic to symptomatic hereditary syndromes. Across this scale there are varying symptoms which are not consistent across each categorisation. This varied presentation can increase time to diagnosis and often limit clients from receiving the care required.

What is Hypermobility?

Hypermobility is where joint/s move into a greater range of motion than normal or expected due to changes within the bodies connective tissue. Without pain this is known as asymptomatic hypermobility. In symptomatic hypermobility disorders, there is the presence of chronic or acute pain and additional symptoms such as fatigue, dizziness, gastrointenstinal dysfunction, headaches and anxiety. This spectrum is not linear, with symptoms and severity varying across the population.

The classifications of hyper mobility disorders are as follows:

| Joint Hypermobility Syndrome (JHS) | Symptomatic hypermobility Absence of genetic hypermobility |

| Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders (HSD) | Positive 2017 HSD criteria Further classification into 4 subgroups: 1. Generalised: all joints 2. Peripheral: hands and feet 3. Localised: one area of joints affected 4. Historical: history of generalised hypermobility |

| Hypermobile Ehlers Danlos (hEDS) | Positive 2017 hEDS criteria |

| Ehlers Danlos Syndrome type 3, hEDs, HSD | Hypermobile with additional systemic changes Positive Beighton score Positive Brighton score HSD and hEDS criteria |

| Possible/probable connective tissue disorder | Connective tissue affected No known cause or specific diagnosis |

| Undefined suspected connective tissue disorder | Further investigation required Suspected hypermobility without diagnosis against existing criteria |

Symptoms:

Identifying hypermobility syndromes goes beyond the presence of painful increased joint range of motion. Some patients will not be aware of the term hypermobility and use alternative descriptors such as being double jointed. Patients may report any of the following symptoms:

- Being double jointed

- History of joint subluxation or dislocation

- Repeat dislocations

- Multi-joint pain

- Bruising easily

- Fatigue

- Anxiety

- Headaches

- Depression

- Stretchy skin or unusual stretch marks

- Urinary or bowel dsyfunction including incontinence

As secondary symptoms are systemic and varied, it is often difficult for individuals to recognise the relationship with hypermobility. Your clinician will gain as much information as possible to facilitate further diagnostic tests and investigations as required.

Diagnosis

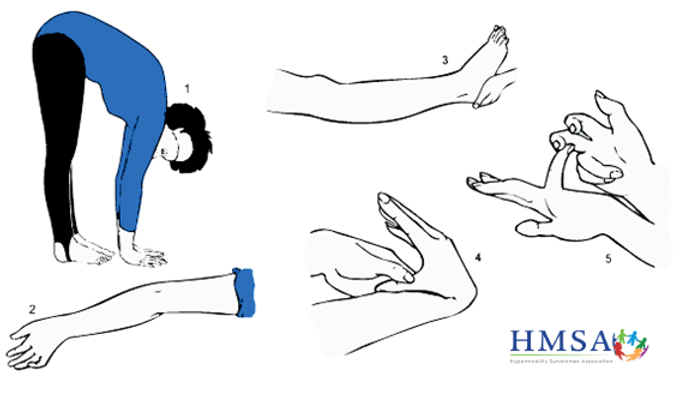

During the subjective, your Physician or Physiotherapist will discuss your presentation and utilise screening tools to guide diagnosis. The first criteria is the Beighton Score which detects generalised hypermobility through 5 postures:

- Forward bend maintaining straight legs and palms onto the floor

- Elbow hyperextension

- Knee hyperextension

- > 90 degrees of passive 5th MCP extension

- Thumb opposition to the forearm

For those not able to complete a physical assessment, the 5 point questionnaire is a self-reported diagnostic tool based on the Beighton score. These tests in conjunction with screening for additional musculoskeletal involvement is used to diagnose generalised hypermobility. A positive score is that of 5 and above.

As mentioned, the diagnostic criteria for Hypermobile EDS goes beyond a positive Beighton score with systemic organ changes, family history, musculoskeletal changes and diagnoses of exclusion. The checklist will often be completed with a Physician, an example form can be found through on the Ehler’s Danlos Society website.

What is Ehler’s Danlos Syndrome?

Ehler’s Danlos syndrome (EDS) is a collection of inheritable connective tissue disorders, 13 to be exact. Joint hypermobility exists in most types of EDS however not everyone with EDS will exhibit joint hypermobility. Hypermobile EDS is the most common form of EDS accounting for 90% of diagnoses. Skin changes are also a key feature of EDS. Skin hyperextensibility (stretch) is greater than 1.5cm and can increase beyond this in specific EDS sub-types. Other changes include fragility of the skin, increased timeframe for wound healing and unusual scarring.

As there are 13 different classifications of EDS, each presentation and primary symptoms vary between cases. This article will discuss Hypermobile EDS in the context of hypermobility disorders in further detail.

Cause

The cause of HSD is largely unknown with inconclusive and inconsistent findings with genetic testing. There may be a weak inheritance pattern or gene mutation seen in some cases however a clear link has not yet been made.

There is a genetic variance in EDS that impacts the gene responsible for connective tissue. This variance is inherited by one or both parents. The gene variation may not be expressed in all cases and there are rare instances where variation can occur without inheritance.

Management

Management for individuals with EDS or HSD is multi-disciplinary in it’s approach. Management typically starts with a General Practitioner to coordinate the involvement of allied health faculties including Physiotherapists, Occupational Therapists, Pyschology and Dieticians as required.

Your GP will also assist in creating pain-management plans and monitoring for changes in symptoms across all body systems. This includes education regarding activity pacing, sleep hygiene, exercise, participation in sport and monitoring behavioural or cognition changes.

Physiotherapy Management

Physiotherapy plays a key role in the management of painful and unstable joints as specialists in biomechanics and movement education. Your treating Physiotherapist will identify which joints are specifically affected from a hypermobility and functional perspective. Typically joint stabilisation exercises are focused around the shoulders, knees and hips. By building the strength and stability of the surrounding musculature there is reduced risk to the joint. So how much strengthening and what training style should Physiotherapists use?

Anecdotally, I have found myself historically leaning to isometric, high repetition, low load strengthening in this population when I first began working as a Physiotherapist. As my caseload began to increase with paediatric- adolescent presentations of HSD and EDS I began questioning why this ‘gentle strengthening’ selection had been made. The research demonstrates that this is not uncommon, the complex pain presentation, fatigue and additional conditions such as POT’s does create a challenge to develop a goal based but achievable exercise program.

Liaghat et al. conducted a study in 2021 assessing high load versus low load strengthening in a HSD population with shoulder pain due to the high prevalence of shoulder pain in HSD and EDS individuals. This study found that patients reported greater shoulder function however there were no statistically significant benefits in shoulder strength. Whilst not statistically significant, there was notable improvement in strength, proprioception and joint instability. An important consideration raised in this study were the reported adverse effects in the high load group of headaches and muscle soreness- symptoms experienced commonly in this population group.

So how does this information impact on Physiotherapy intervention? Recognising the variability within this population group is as important as any other presentation. If you have a client presenting with HSD, POT’s and significant amounts of musculoskeletal pain, commencing with light load and isometric style strength training may be a great place to start. If you were to introduce a high resistance training protocol which has a likely pathway to increasing headaches and joint pain, the impact on rapport and patient buy-in is an important consideration. Once joint control and proprioception begins to increase, progressively grading in high resistance training is a great option. I have also had young male clients that have been out of typical sport activities and are itching to get back into a gym space and therefore, much more responsive to high resistance, low load training. Dependent on the patients goals, capacity and occupation/daily demands, this approach may also be much more valuable to increase muscle strength to further joint stability.

Further research into this area of rehabilitation will continue to guide clinicians and their clients through rehabilitation and exercise management.

Key points:

- HSD and EDS presentations exist on a spectrum.

- Symptoms are not exclusive to increased joint range of motion.

- If you have a client with a positive Beighton score, investigate the presence of other systemic changes to guide diagnosis and refer on.

- If you have HSD, ensure you are working with a treating team that includes Physiotherapy.

- Exercises for strengthening, joint proprioception and stabilisation are an important part of management.

References:

- Hypermobility Syndromes Association. “hEDS, JHS and HSD”.

- Hakim, A. J. (2017). A clinicians guide. The HMSA.

- What is HSD?. The Ehlers Danlos Society. (2023, December 12).

- Australian Rheumatology Association and Arthritis Australia. (September 2022). Adult hypermobility spectrum disorders – Patient Information.

- Nicholson, L. L., Chan, C., Tofts, L., & Pacey, V. (2022). Hypermobility syndromes in children and adolescents: Assessment, diagnosis and multidisciplinary management. Australian Journal of General Practice, 51(6), 409–414.

- Kumar, B., & Lenert, P. (2017). Joint hypermobility syndrome: Recognizing a commonly overlooked cause of chronic pain. The American Journal of Medicine, 130(6), 640–647.

- Zabriskie HA. Rationale and Feasibility of Resistance Training in hEDS/HSD: A Narrative Review. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2022 Aug 20;7(3):61.

- Liaghat B, Skou ST, Søndergaard J, et al. Br J Sports Med Epub. 2022. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2021-105223