The diagnosis of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) can be overwhelming. It can make you question how your pelvic floor will function, child-bearing plans, continence and the impact on physical activity and sex. This article aims to explain the pelvic floor, its function, what prolapse is and what treatment options are available.

What is the pelvic floor

The pelvic floor does not exclusively refer to the muscles of the pelvic floor but the all the structures located within the pelvis. This includes the organs, muscles and their connective tissues, blood vessels and nerves. The muscles and fascia work together to provide support to the pelvic organs and maintain continence.

There are superficial and deep muscle layers that make up the muscular support system. The Levator Ani and Coccygeus are the deepest muscles of the pelvic floor. These provide the most amount of upward support and maintain the anorectal triangle. The layer closest to the skin are the superficial layers which are made up of the urogenital triangle and external anal sphincter. There are sub components of the levator ani and the urogenital triangle with complex muscular layering. The muscles are reinforced by the endopelvic fascia to maintain the position of the bladder, vagina and rectum.

A normal functioning muscular and fascial system provides support for the pelvic floor and ensures appropriate timing for contraction during periods of increased abdominal pressure ie. coughing or sneezing. Conversely it will facilitate a normal resting position and at relaxation. “Normal” pelvic floor function is dictated by muscle activity at rest, fascial support and anatomical position.

Muscles and Fascia

The levator ani plays a key role in the suspension of the pelvic organs. This muscle group forms a sling around the rectum. During contraction, puborectalis creates a kink at the anorectal angle as the levator ani moves up and forward (towards the pubic bone). During contraction as the levator ani moves forward, it creates a secondary closure mechanism for the vagina via the posterior wall. Relaxation is the inverse movement of the pelvic floor musculature and bears equal importance to contraction. Relaxation facilitates opening of the exiting to allow for release from the bladder and bowel as well as penetration.

In addition to the pelvic floor muscles and their position, the fascial/ligamentous structures play an equally important role in supporting the pelvic organs. There is the retrovaginal and pubocervical fascia, uterosacral and cardinal ligaments which provide passive support to the pelvic organs and are reinforced by the pelvic floor muscles.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Pelvic organ prolapse is a condition experienced by over 40% of women. To put into perspective 1/4 athletes and 1/3 women who have given birth. As aforementioned, the pelvic floor supports the pelvic organs; bladder, vagina and rectum which lie respectively from the pubic bone to the coccyx. Each pelvic tract has an area for storage and an area for release.

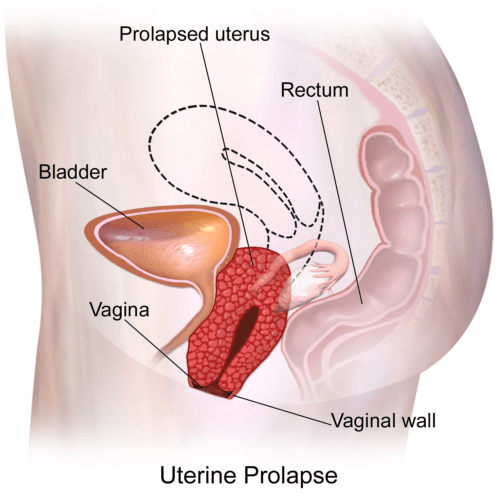

POP is where there is slipping of the pelvic organs out of place. The bladder, uterus and rectum can all slip into the vagina to varying degrees based on the POP-Q classification system. This dictates the degree of descent. When diagnosing the organ involved the following terms are used: bladder prolapse/cystocele, rectal prolapse/rectocele, uterine prolpase, vaginal vault and small intestine /enterocele. Further classification and understanding of the function of the pelvic floor is assessed during an internal examination.

It is important to note that the slipping that occurs during POP does not indicate failure of the organs but the support systems (pelvic floor muscles and the fascia).

Pelvic floor muscle factors associated with POP:

- Weakness

- Rupture of the pelvic floor muscles

- Anatomical variances: large levator hiatus at rest

- Ballooning of the levator hiatus on effort

Additional contributing factors:

- Vaginal birth, increased with instrumental delivery

- Genetics

- Family history

- Hypermobility and connective tissue disorders

- Obesity

- Chronic constipation

Symptoms

Symptoms of POP do vary dependent on the organs involved and the severity of the symptoms. Some or all of the following symptoms may present:

- Bulging

- Pelvic pressure

- Lumbar spine aching

- Sensation of heaviness or dragging

- Bleeding, discharge or infection

Regarding each pelvic organ system:

- Urinary symptoms: hesitancy, position dependent emptying, slow stream, straining, intermittency, leakage post emptying, increased frequency and a sensation of incomplete emptying.

- Anorectal symptoms: constipation, relying on techniques such as splinting or digitation for defecation, urgency, sensation of blockages, straining, feeling of incomplete emptying and soiling post defecation.

- Sexual symptoms: painful penetration, thudding pain, deep pain, obstructed intercourse.

Assessing POP

To assess POP, your Gynaecologist, General Practitioner or women’s health Physiotherapist will complete an internal examination using a speculum or digitation of the vagina and rectum. This will aid the visualisation of the anterior and posterior vaginal wall to determine slipping of the bladder, uterus or rectum. Whilst being able to grade the POP, the examination will also rule out pelvic masses, degree of vaginal muscle loss and other pathologies.

The POP-Q measuring system allows clinicians to then classify the degree of displacement and provide relevant education, advice and treatment options. The five stages from 0-4, refer to the displacement relative to the hymen. The length of the vaginal canal is 8-10cm long, thus stage 0 could be recorded as -8cm and stage 3 +2cm. Anything protruding >2cm beyond the vagina is a stage 4.

Treatment

First line intervention for women with symptomatic stage one or two POP is a 16-week supervised pelvic floor muscle training program. Conservative management can improve symptoms in 1/3 of women with the most common improvement noted with urinary incontinence. Clinical studies have demonstrated improvements in prolapse grade and symptoms in stage one and two up to 6 and 12 months post- supervised intervention. In this Note that women with stage three POP did not experience a change in grading/anatomical position but symptom improvement. Other lifestyle recommendations exist for POP based on clinical reasoning including: weight loss, constipation management and reducing excessive or heavy lifting.

In addition to pelvic floor strengthening and education, a Pessary may be suggested by your treating Physician or Physiotherapist. Further information on Pessary fitting can be found here.

If conservative management is not effective or the severity of POP is greater than a grade 3, surgical intervention may be recommended. A multitude of factors must be considered before having surgery including age, future pregnancies, activity levels and health status. The goal of surgery is to lift and reposition the pelvic organs that have slipped and reinforce the support structures using existing tissue or mesh. Types of repairs include:

- Anterior or posterior vaginal repair: in an anterior repair the bladder is reinforced to reduce the pressure onto the anterior wall of the vagina. Similarly, the posterior repair lifts the rectum to reduce the posterior slipping into the vaginal wall.

- Sacrocolpopexy and sacrohysteropexy: these repair protocols use the sacrum as an attachment site for either the vagina or the cervix when the uterus has slipped down.

Vaginal wall repair surgery using organic tissue can reduce symptoms in 90% of women and similar success rates exist in women undergoing a uterine prolapse repair. Synthetic repair using mesh may be considered when the quality of the organic tissue isn’t suitable or repeat prolapse post-repair has occurred. Mesh repairs are used cautiously due to the adverse effects such as vaginal wall erosion, bladder injuries, urinary incontinence and persistent pelvic pain. Those women experiencing these side-effects following a mesh repair have endured financial, psychological and physical trauma that must be acknowledged. This is an important consideration with treatment for women suffering from pelvic pain and trauma.

Beginning to work with a women’s health Physiotherapist is recommended to provide education, exercise therapy, lifestyle advice and access to support services when required.

References:

- InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006. Surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. 2018 Aug 23.

- The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists, Surgery for Pelvic Organ Prolapse, FAQ. Last updated: July 2022.

- Maher, C., Baessler, K., Glazener, C.M.A., Adams, E.J. and Hagen, S. (2008), Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women: A short version Cochrane review. Neurourol. Urodyn., 27: 3-12.

- O&G Magazine. Croft S, Physiotherapy after mesh complications.

- Brunes, MP, Ek, M, Drca, A, . Vaginal vault prolapse and recurrent surgery: A nationwide observational cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022; 101: 542– 549.