This article will discuss some of the most common pathologies presenting in dancers that involve the foot and ankle joint. Injuries to the lower extremity in dancers are more common than upper limb injuries due to the amount of range and force required to perform particular movements.

Common Injuries:

- Posterior ankle impingement

- Base of 5th metatarsal fractures

- Flexor hallucis longus tendinopathy

Posterior Ankle Impingement (PAI)

The prevalence of ankle injuries range from 4.7-31% of all dance-related injuries. During dance, the ankle is quite often held in an elevated position known as ‘releve’. In this position the ankle mortise is placed into excessive plantar-flexion and overtime can cause compression of the structures behind and deep in the ankle joint. These structures include the posterior talocalcaneal ligament, the achilles tendon, posteromedial tibiotalar capsule and posterior fibres of the tibiotalar ligament. Their location between the talus and medial malleolus predisposes to the entrapment during plantar-flexion. This occurs during a demi-pointe (soft slippers) and is heightened whilst en-pointe (pointe shoes). Posterior ankle pain can be caused by the repetitive compressive forces to the bony and soft tissue structures.

Soft tissue

- Cysts eg. ganglion cysts

- Tendon friction

- Excess fluid in the synovium (joint capsule)

- Recurrent ankle sprains resulting in ligament laxity

Bone (osseous)

Formation of bony processes can occur at the end of the talus offering potential cause for compression. This process can occasionally harden, forming separately from the talus called the “os trigonum”. The os trigonum is the most common cause of symptomatic posterior ankle impingement

Clinical findings

On examination, the following findings may present in those with PAI.

- Pain with plantarflexion +/- overpressure from the therapist

- Symptoms may be insidious in onset or in response to a traumatic event or acute injury to the ankle

- Area of pain on palpation of the medial or lateral ankle malleoli

- Complaints of pain while on demi-point or en-pointe

Those with PAI, also complained of reasonable to severe pain with daily activities and sport performance.

Imaging

X-rays (in weight-bearing) are routinely performed on dancers if they present with findings consistent with PAI. This is to identify the possible bony catalyst for pain. Further imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess the internal joint capsule around the talus may be required. The decision for imaging will be reached by your treating therapist in conjunction with your General Practitioner or Sports Physician.

Treatment for PAI

Treatment for PAI involves a trial of conservative treatment before surgery is then looked at. In the initial stages of PAI, the athlete will rest and reduce the aggravating activity to settle inflammation and pain.

Appropriate manual therapy such as joint mobilisations and soft tissue intervention to improve ankle mobility has been shown to ease symptoms in the initial stages. Unfortunately, evidential support of conservative treatment is limited in this population with further studies required.

Exercises to strengthen/stretch the surrounding lower limb musculature is important while in a period of active rest from sport/dance to preserve strength and length to the lower limbs for return to sport. Some examples can be seen below. This should always be conducted under the guidelines of your treating Physiotherapist.

In certain cases, an injection of a steroid solution into the posterolateral ankle can be utilised in the early phases for severe pain management under the guide of your Physician or Orthopaedic Surgeon. This should be completed in conjunction with Physiotherapy treatment for optimal outcomes. Surgical intervention for bony formations may be indicated in cases of high levels of pain and discomfort. Recent evidence support surgical intervention for PAI with an arthoscopic procedure to remove osseous formations which demonstrated symptom improvement in 85% of cases.

Metatarsal fractures

Metatarsal fractures are very common amongst dancers, accounting for 63% of all fractures in female dancers. This is usually put down to the repeated excessive forefoot loading that dancers are known for when en pointe and demi-pointe. Non-mechanical risk factors for metatarsal fractures can include bone-density (linked to poor diet), amenorrhea (abnormal/missing menstrual cycle) and eating disorders. These three factors are known as the female athlete triad.

Female Athlete Triad (FAT)

Treatment effectiveness for stress fractures linked to the FAT requires addressing all three of the triad’s components: eating disorders, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis (bone density). Failure to meet nutritional demands and fuel efficiently can impact hormonal balance and available energy/minerals for bone health. Stress fractures can subsequently occur and should be closely monitored in this population.

According to research by Nose-Ogura et al., patients who have one FAT component, have a 2.5 times higher chance of developing a stress fracture. This ratio increases to 4.7 times more likely if they have two or more FAT components.

Reducing the risk of these fractures is possible, it involves a pre-participation screening for the presence of FAT symptoms and includes keeping track of body weight, energy level, menstrual cycles, and bone mineral density regularly. This ensures these elements can be actioned and referred onwards if picked up in pre-screening.

Imaging

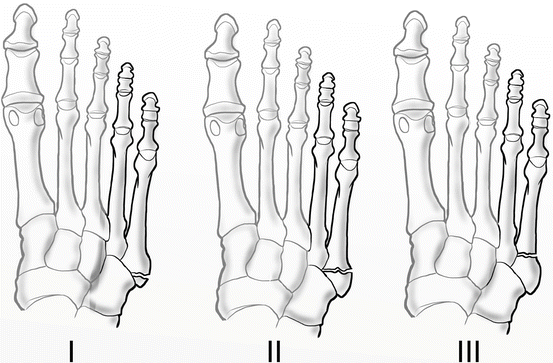

Base of the fifth metatarsal stress fractures classify into three types based on the Torg classification system:

Zone I:

- Narrow fracture line with sharp margins and no widening

- Known as pseudo-Jones fractures or tuberosity avulsion fractures

- The mechanism of injury is usually with landing in plantar flexion forces the hind foot into inversion

Zone II:

- Wide fracture line with adjacent lucency

- Involves both cortices

- Mechanism typically involves quick direction change with significant adduction force to the foot with a raised heel (on demi pointe)

- Non-union rates for these fractures are up around the 15 to 30% mark

Zone III:

- Wide fracture line

- Periosteal new bone formation

- Complete obliteration of the medullary canal by sclerosis

- Stress type injuries that worsen with activity over numerous months/years

- These fractures carry a higher risk of non-union than zone 2 fractures

Prognosis

Most of the acute, non-displaced fifth metatarsal fractures recover with conservative management in 6 to 8 weeks. Zone 2 and 3 fractures show higher non-union rates due to poor vascular supply. See the following for conservative management and the role of Physiotherapy.

Treatment

Zone 1: managed conservatively with a period of protected weight-bearing (on crutches) while wearing a walking boot or a hard soul shoe/orthotic. Weight bearing can begin once pain and symptoms improve.

Zone 2: managed conservatively with 6 to 8 weeks of no weight bearing in a short leg cast. Weight bearing commences with signs of radiographic bone healing. Athletes/dancers who sustain this fracture may opt for immediate surgical intervention or if the displaced fracture requires fixation.

Zone 3: consists of a trial of conservative management that involves non-weight bearing in a short leg cast. These fractures may take up to 20+ weeks of immobilisation before there is noticeable radiographic union. In some instances the healing can be problematic for function. Surgery is required for high-performance athletes.

Physiotherapy/rehabilitation

Phase 1

- Range of motion (ROM) exercises

- Training for assistive devices and orthotics

- Pain management and oedema

Phase 2

- Continue ROM exercises

- Resistance exercises

- Strength training of lower limbs

- Manual soft tissue release and scar management (post-operative)

- Continuing gait training

Phase 3

- Full ROM of ankle and foot

- Progression of resistance exercises

- Stability and proprioceptive drills

- Emphasis of normalising gait pattern without any aids

- Sports specific movements and drills if an athlete

Flexor hallicus longus tendonitis/tendinopathy (FHLT)

Ballet dancers spend a lot of time en-pointe which involves sustained ankle plantarflexion with repetitive fluctuation from plantarflexion to dorsiflexion (en-pointe or demi pointe). The tendon of flexor hallicus longus (FHL) runs from the medial calf, through the tarsal tunnel (medial ankle) and under the foot into the big toe. Repetitive tendon gliding with the aforementioned movements can cause tendon inflammation resulting in restricted range of motion, pain or discomfort.

Symptoms/clinical findings

- Pain and swelling at the posteromedial aspect of the ankle

- Complaining of a “stuck” feeling in the back of the ankle

- Pain increases with demi-pointe, en pointe and jumping

- Pain at the posterior ankle when moving the big toe up and down

In chronic and severe cases there can also be tendon stenosis/narrowing. The great toe may become stuck or frozen in the plantar-flexed position. This is referred to as “Trigger Toe”, which requires manual or surgical release of the contracture.

Diagnosis & Imaging

A thorough patient history in conjunction with an objective examination is vital for correctly diagnosing this condition. MRI may be used to rule out any tears or signs of impingement. Ultrasound can also provide information on the status of the tendon. X-rays are not utilised for diagnosis.

Treatment/management

Treatment involves education and conservative management with rest, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, manual therapy and strengthening exercises. Your Physiotherapist will work within the parameters of pain and inflammation to guide treatment response and progressive loading.

Soft tissue massage and joint mobilisation of the subtalar and the first metatarsal joint can aid mobility when used in conjunction with a strength and mobility program. Strengthening should also target surrounding musculature to address strength deficits or mal-loading that has occurred as a result of the injury. Ultrasound is a modality that has some merit in reducing pain when included in a well rounded treatment protocol.

Strengthening exercises for FHL includes: isometric, eccentric and isotonic movements dependent on the stage of rehabilitation. Isometric exercises tend to play a larger role in the early stages of rehabilitation to build tissue tolerance. Other exercises include: FHL tendon gliding exercises, big toe resisted flexion/extension/inversion, toe towel grabs, gradual loading into demi-pointe and en-pointe positions. Your Physiotherapist will be able to provide a tailored exercise program based on your goals and level of performance.

The video below demonstrates some exercises that our clinicians have provided for this condition. Exercises shown are general in nature and should only be completed under the guise of your treating therapist.

References:

- Moser BR. Posterior ankle impingement in the dancer. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 2011;10(6):371-377.

- Foster T, Bickle I. 5th metatarsal fracture. Radiopaediaorg. 2016.

- Rehmani R, Endo Y, Bauman P, Hamilton W, Potter H, Adler R. Lower Extremity Injury Patterns in elite ballet dancers: Ultrasound/MRI imaging features and an institutional overview of therapeutic ultrasound guided percutaneous interventions. HSS Journal. 2015;11(3):258-277.

- Feingold D, Hame SL. Female athlete Triad and stress fractures. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 2006;37(4):575-583.

- Nose‐Ogura S, Yoshino O, Dohi M, et al. Risk factors of stress fractures due to the female athlete triad: Differences in teens and twenties. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2019;29(10):1501-1510.